Consequential Innovation, The Falsity of the Digital Frontier, and the Sobering Presence of Safiya Umoja Noble

If Dr. Safiya Umoja Noble were a road sign, she would read: “CAUTION: Slow Down, Sharp Curve Ahead”. She is the person who asks if we are headed toward a cliff while everyone else is blindly engaged in winning the race. She is a sobering and questioning presence in a time of great, almost delirious, innovation.

As a scholar who explores and defends the intersection of technology and social justice, Dr Noble is a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). She teaches Gender Studies and African American Studies and is the faculty director of the Center on Digital Race and Justice. She is a MacArthur Foundation Fellow and the recipient of the NAACP-Archwell Digital Civil Rights Award. She also authored the best-selling and critically acclaimed book, “Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism,” which exposed the racist and sexist biases that exist in commercial search engines.

On Tuesday, June 06, 2023, the second day of DrupalCon-Pittsburgh, Dr. Noble gave a keynote presentation on systemic biases in technology, and the great responsibility of web developers to build tools that protect and promote the welfare of our society. DrupalCon is one of several annual gatherings of a tech community that is united through the open-source software Drupal.

“This may make me an unsatisfying dinner party guest,” Noble said, as she proceeded to lay out the shortcomings and dangers of modern technology to a room of thousands of experts, enthusiasts, and professionals in that field.

She illuminated the hypocrisies of overarching narratives that have been widely adopted by the tech community—myself included. I understand now how these narratives propel reckless innovation, and for that reason, I will explain where my own mindset came from, and why it was a deception.

In my white, socioeconomically stable, American male mind, I spent many adolescent years cultivating an unwary and innocent sense of hope. Hope for the future, hope for me. A hope that was fostered in the luxury of discovering our societies’ ailments both conceptually and at my own pace. A hope that permeated outward and transformed into a sense of excitement in the unknown, and in that which would seem most likely to ‘change the world.’

This excitement drew to form in technology. In a predictably human way, I attributed a specialness to the time and place in which I was born. For me, that was as an early member of the turn to the second millennium – a silver-chrome era that had been foreshadowed by the rise of computing during the final decades of the 20th century.

As the calendars ‘ones’ became ‘twos’, this period was coined the “Digital Age”. Like those early Americans who marveled at the thought of westward expansion, my eyes twinkled at the idea of technology as a second frontier on which we could build our brave new world.

Aldous Huxley’s technologically dystopian novel, “Brave New World,” shares a theme with Safiya Noble’s research, though Noble prefers to avoid the “doomsday” criticisms: encased in seemingly great innovations often exist gravely dark realities.

No action is without consequence, and as we charge forth with zeal toward a seeming ‘promised land’, one must remember the impacts of the world they are creating.

I shared my original sentiment with Dr. Noble, about technology as a new frontier, after her keynote address.

“It’s so interesting,” she responded, “the metaphor you use is one that often gets used around A.I. (Artificial Intelligence)—the idea of a ‘New Frontier’—an open expanse, or vast emptiness. But of course, we know that this is a colonial perspective. The ‘frontier’ already had people who were living on the land. It was not free for the taking.”

The stained glass cracked. I was struck by the reminder that the glorification of the ‘frontier’—of the American cowboy and Manifest Destiny—was a falsehood spread by the American government, profited off of by Hollywood, and perpetuated by the United States education system to validate and mask a bleak history of theft, destruction, and violence. To use it as a metaphor for technological innovation seemed like an obvious misstep, but it was one that had not yet occurred to me.

Dr Noble continued on to identify the more shadowy extremities of the tech giant:

“These metaphors obfuscate things. There are thousands and thousands of people doing extremely exploitative, low-wage labour outside of the United States… cleaning data, moderating content, putting together microprocessor chips, going through e-Waste, mining minerals like Coltan and the other minerals needed to make electronics… all of that is work that [Big Tech] outsources, and takes the largesse—the benefit—from, then narrates to us as emancipatory.”

Not unlike the idealisms purported in Manifest Destiny—that Americans had the God-given right to push forth and claim the land that was naturally theirs, from ‘sea to shining sea’—the tech sector often presents their innovations as great steps forward for humankind, an “emancipation”, as Dr Noble calls it. Less often do they take credit for the harmful byproducts of these innovations.

She continues,

“These products are grifting all kinds of copyright, art, and other public goods, then pulling it into their systems as if they were open and free for the taking when they are not. The mental model around many of these projects is the same mental model of the past. And it’s reproducing the same kind of inequities.”

The preservation of our socioeconomic caste, or the reproduction “of the same kinds of inequities,” as Dr Noble put it, is one of the significant dangers technology presents. She explained how Artificial Intelligence—a hot topic, not only at DrupalCon but in the global conversation—will contribute to this process.

As a university professor, Noble described how higher-education institutions have discovered the potential of A.I. to alleviate their most pressing problems, such as increasing enrollment, improving student retention, and allocating financial aid.

In this article published in Forbes, Michael T. Nietzel, President Emeritus at Missouri State University, describes how an AI technology company named Aible was hired by a mid-sized University to improve the targeting of prospective students who the university would reach out to.

The A.I. technology would sort through large pools of student data and

“identif[y] a subset of applicants who—based on their demographic characteristics, income levels and family history of attending college—were most likely to respond to well-timed phone calls from the faculty.”

The preliminary results of this action showed a 15% increase in that universities’ enrollment yield.

Many of the academic clients of Aible, of whom founder Arjit Sengupta said there were 5 to 10 at the time of publishing, opt to remain anonymous in their use of A.I. This is likely due to concerns over data privacy violations and the exclusions of large student populations which inherent biases in these systems produce.

Despite recognizing these issues and deflecting responsibility for them, universities still use the technology because its convenience and effectiveness are too great to pass up. During her presentation, Dr Noble broke down exactly how these technologies might exclude student populations from receiving such a “well-timed call” from a university.

When you ask an A.I. program to survey data and define a ‘model student’ who would predict which applicants will enrol and stay enrolled, Noble says the student is likely to share these three traits:

- Their parents also went to college.

- They can afford to pay for college without a job on the side.

- They live on campus at the university.

These categories exclude first-generation students, students who have to balance schoolwork and a job, and students who can’t afford to live on campus; all three of which face a more difficult route to simply being a student at all.

“All these things,” Noble continues, “when you add them up and put them into a predictive analytic… you see that they only reproduce, and give opportunity and access to, the people who generationally have already had it.”

After describing how Artificial Intelligence can perpetuate our societies’ inequalities, Noble pivoted to a different threat which tech presents—one that is of a more epistemological nature.

“If I were to say there are two communities who are most critical in this moment we’re living through, it would be developers/programmers/computer scientists, and librarians. Both sets of workers have an incredible responsibility to society to help us know, to help us learn, and to help us find our way through.”

It can be extremely difficult, with the masses of digital information we are approached with each day, to know what is an opinion, what is a fact, and what is fiction. We use the web as a tool to understand the world, people, and events outside of our immediate surroundings, but when the web is contaminated with lies, misinformation, and malicious actors, our shared reality as a society of users is threatened.

“We are working in the sphere of information,” Noble said, “what people call ‘content’. That, unfortunately, is also the place where things like propaganda live.”

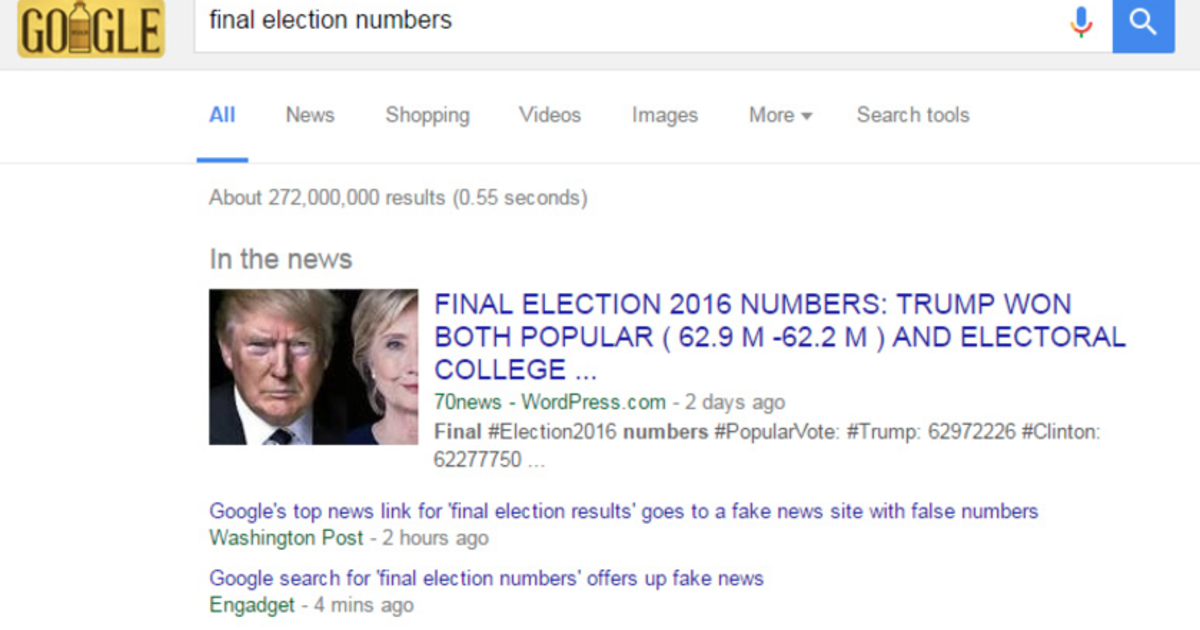

In her presentation, Noble noted a recent span of history when Americans became particularly unsure of who and what to believe on the internet.

On-screen she displayed a headline that was widely circulated and covered by mainstream media after the 2016 American presidential election. It was an article that said Donald Trump had won the popular vote—which he had not, he won the electoral vote—and it used an inaccurate tweet as its source.

Though it may seem like a “banal” occurrence, as Safiya put it, when there are many instances like this, people become increasingly frustrated with the lack of stable facts to communicate with.

For four years of his presidency, Donald Trump stoked these frustrations. He criticized and undermined the mainstream media with self-protecting lies and verbal attacks. Many Americans felt forced to take a side—either believe Donald Trump and revoke most mainstream publications, or deny the credibility of their President. There seemed no middle ground.

This warfare all took place in the digital world. Twitter was flooded with hostility and lies. Anonymous image boards and blog post sites, like 4Chan, became a breeding ground for dark conspiracy theories like QANON. Day by day, agitation in our citizens accrued from what they were seeing on their televisions, cell phones, and computers.

Finally, these small occurrences compounded into one large, violent event: the riots on the American Capital Building on January 6th, 2021. Far-right extremists from around the United States had found each other online and shared disgust over the conspiracy that the presidential election had been stolen from Donald Trump—a lie which Trump widely promoted.

In an act of violent protest, hundreds of armed citizens arrived in Washington D.C. and stormed the Capitol Building. The lives of civilians and law enforcement officers were lost in the process.

Yet, such a significant event did not cause a large shift in the public conversation. Many people still denied the election results, and propaganda was widely spread across social media, further dividing our citizens on what was true and what was not.

“You would think,” said Dr Noble, “that the January 6th uprising against the United States government—the murder of law enforcement officers, and the attempts to murder public officials—would have been a moment of deep relief, where people would have said ‘enough.’ Yet, the propaganda machine kicked in, and has really neutralized, in many ways, what it means to have people attempt to overthrow the United States government.”

Though there is not a simple explanation for how instances like these can be prevented, they highlight the seriousness of a web developer’s responsibility. There is not a clean-cut separation between the ‘real world’ and the ‘digital world’. We make sense of the real world in the digital world, and when one is corrupted, it spills over into the other.

In covering a previous story on an energy executive who claimed to be mischaracterized by a national health agency, a quote from Thomas Sowell, the American economist and author, was used: “There are no solutions, there are only trade-offs.”

Similarly, Dr Noble advises web developers that there is no software that is without bias.

“Where there is a point of view, always, there is a set of priorities. So, the question is,” she asks, “what are we biasing toward, and what are the values that we care about?”

One solution Noble offers is to include social scientists as peers in the software development process.

“Bring in PhDs in Gender, African American, Ethnic, and American Indian Studies—people who have deep expertise in a variety of ways… If you are designing technology for society, and you know nothing about society, then we’re in trouble.”

There is no absolute right answer. There are only actions with varying degrees of consequence. Developers must understand what they are creating, why they are creating it, and what the product’s presence will mean for our society.

They would be wise to heed the advice, and perhaps ask the help, of someone whose expertise lies in an area outside of their own.

Note: The vision of this web portal is to help promote news and stories around the Drupal community and promote and celebrate the people and organizations in the community. We strive to create and distribute our content based on these content policy. If you see any omission/variation on this please let us know in the comments below and we will try to address the issue as best we can.