I Am Not Your Statistic: Killing User Personas and Reimagining Consumers

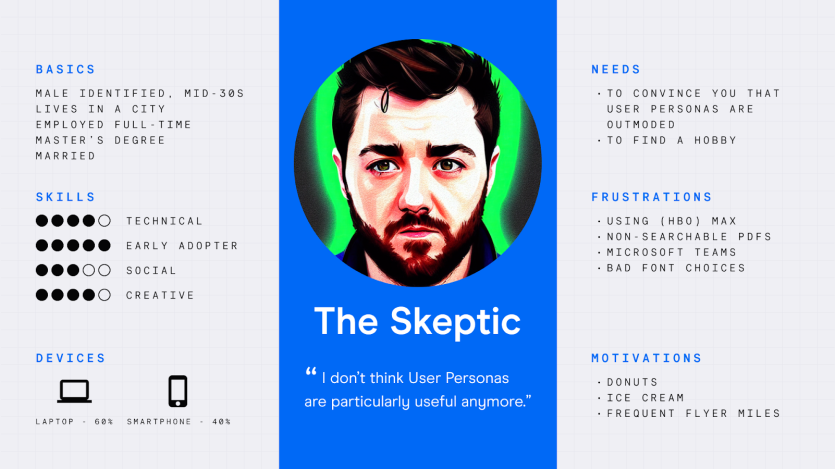

Elliott Mower, the Head of Product at Mediacurrent, is a white-collar male, a millennial with a high technological acumen, and is likely to be an early adopter of new technologies.

If you are working in the field of product design, say, building a new software for shopping on your phone, and think Elliott is a potential consumer, you would almost certainly be advised to use this information to build a user persona. That persona would then guide the way you would build your product.

But are these the characteristics—gender, age, technical ability, education—we should be using to try and build our customers the best products possible? Elliott Mower would posit that they are not. In fact, he would posit that these characteristics can be misleading, and are ultimately beside the point.

In other words, Elliot Mower feels the traditional model of a consumer persona no longer does its job. As such, it must die.

This is, of course, hyperbolic, perhaps symbolic, and is not a direct quote from Mr. Mower. But it does touch on what he feels is a set of truths about how an industry standard can be improved.

To present his case, Mower first delivered a brief history on the way personas came to be. That story, like many, begins with a person who saw a problem and did something to improve it. That person was Alan Cooper, and Alan was an early software developer in the 1980’s and 1990’s. He noticed that developers were making software for themselves and other developers – not for users.

As software rose in popularity and captured more users, the barriers to entry for these technologies became more consequential. Only developers knew how to use them! Cooper, while building his software, decided he would interview consumers and see what their needs and wants were.

By shifting his inner conversation from one with himself, on what he would like to see most in the product, to one that was instead with potential clients, Alan Cooper initialized the process of creating user personas. This process lists a hypothetical customer’s traits, habits, preferences, and demographics so that a developer can attempt to make a product that suits them.

What’s changed that made this process outdated?

Now, says Elliott Mower, “we are all users.” Back in the day, user personas were about attempting to connect and bridge the gap with a potential consumer whose experience was vastly different from the person who was building the technology. Now, however, almost everyone in society has a significant amount of experience using technology.

“We use software, websites, native apps, and digital kiosks. We interact with technology constantly… User personas were fundamentally about building empathy for people whose experiences interacting with technology were different from our own. To a large extent, that is no longer the case.”

There is a second part that Mower tacks onto that thought: “while we are all users, we [the developers] are not our users. We are creating things for people who are not us, so we have to approach creating them with an equal mix of empathy and objectivity.”

The reason why, in Mower’s opinion, user personas do not achieve this mix of empathy and objectivity, is because the traditional user persona format forces developers to make some “weird and kind of limiting decisions about the people [they’re] building for.”

I am of the opinion that there are countless examples of strife that arise when everyday people use characteristics typical of traditional personas to categorize others and make sense of the world.

The frustrations that arise from these “weird and kind of limiting” categorizations are either in the definer, as their objects defy and scrape against their own assumptions, or in the defined, as they feel pigeonholed by what someone else thinks they should be. I add this short tangent because I think Mower’s call to evolve the way a product developer conceives of a stranger could be more widely applied to the way strangers everywhere try to understand one another. Perhaps, they could approach them “with an equal mix of empathy and objectivity.”

Back to your regularly scheduled programming.

Everyone has limited time and energy. That applies to doing consumer research. Because of this, what often happens when creating personas is a) they are either extremely general (ex: Woman, age 18-34, uses a desktop) or b) they are hyper-specific (ex: 33-year-old woman, 2 children, lives in the suburbs, not an ‘early adopter’ of technology, regularly attends religious services).

The fault in these strategies, says Mower, is that both leave out large portions of the market. A generalized persona, the former, may not account for someone with a motor disability – an example Mower used. A hyper-specific persona, the latter, really doesn’t account for anyone outside of that individual and their ilk.

Wisely, Mower advises a development team to change their questions. These are suggestions he poses:

- How many digital products need to be gender-specific? “Does that really matter for the kind of experience we’re often building?”

- How are we accounting for the spectrum of abilities?

- In a world of responsive design, does specifying devices really matter? “Something that we’re building should work across every single interface that we’re designing for, and ones that we haven’t even imagined exist yet.”

- Is demography destiny or can we separate the things we do from the stats that might appear on a baseball card?

Instead of focusing on “who” will be using a product, Mower advises developers to try and distill “how” the product will be used.

“For the most part when users are engaging with a digital product, they are trying to accomplish something. They might be trying to find a flight, buy a toaster, connect with a friend, or share an experience. If we can define what we think these primary actions are, we can define a user mindset. And the cool thing about user mindsets is that anyone can have them.”

He adds, “our design and development decisions are about making it easier, simpler, and more engaging for a user to reach their goals – whatever their goals may be.”

As an example, Mower defines the kind of questions developers should and should not ask themselves if they were creating a product for someone to learn a new skill.

Things that matter:

- Is this a primary action?

- How long does it take?

- How many steps are in the process?

- Are the steps logical?

- Are there any distractions in the process?

- How satisfying is the end result?

- Is the process repeatable?

- Can the process be completed in one session?

Things that don’t matter:

- Gender

- Age

- Physical and/or cognitive ability

- Device type

- Location

- Education

- Income

- Marital status

- Hobbies or interests

- Brand affiliations

In regard to the items on that second list, Mower says “they do not matter for the thing that we are building. It should just work, and it should just be awesome, no matter what… Whether you use personas or not, you can’t create products for people without trying to understand the people using the products.”

“It’s not ultimately about the tool,” the tool, in this case, being a user persona. “It’s about an intentional, thoughtful, and empathetic process that evolves as people and technology do.”

“I don’t like to shop on my phone,” Mower tells me privately after his presentation, “and I’m a millennial, so you would think I’d be into my phone—I’m really not. So, we just want to make sure that everything we build, everything we design, is maximally intuitive and that it can adapt and be used in any way you want to interact with it.”

In the words of the late Notorious B.I.G. – things done changed… on the web, in its users, and in the world at large. Elliott Mower says to personas, change with it, or die.

Watch the session "Death to Personas: A Mindset-Focused Approach to Designing Inclusive Web Experiences," below:

Note: The vision of this web portal is to help promote news and stories around the Drupal community and promote and celebrate the people and organizations in the community. We strive to create and distribute our content based on these content policy. If you see any omission/variation on this please let us know in the comments below and we will try to address the issue as best we can.